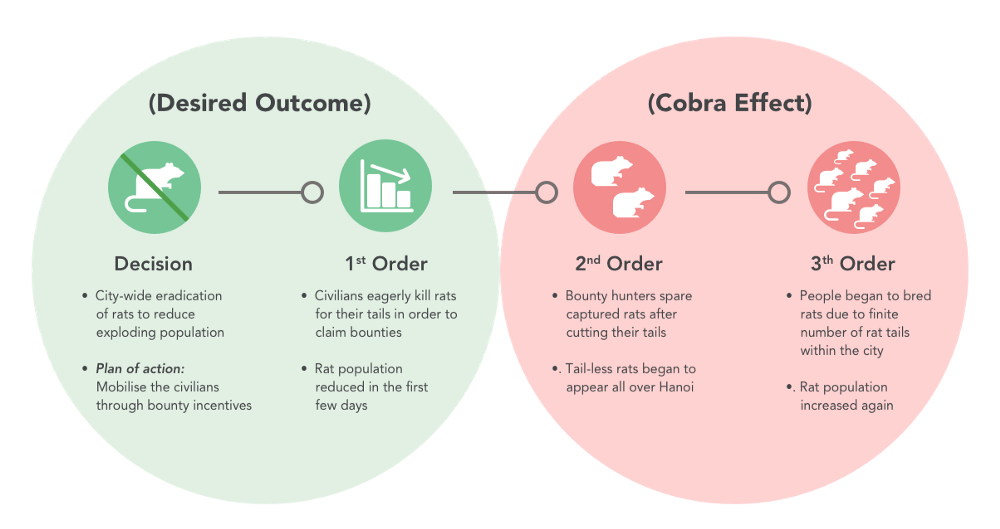

In the early 20th century, the French colonial government in Hanoi declared war on the exploding rat population by placing bounties on these little creatures. All people had to do was to submit the tails of the rats they had killed to claim their reward.

Within days, wave after wave of eager civilians submitted rat tails in droves. While the officials were excited by this development, there were a few twists in the story.

Rats were rampant in early 20th century Hanoi, posing a significant health risk to the population.

Strange sightings of tail-less rats were reported in the city, and people soon realized that it was the work of unscrupulous bounty-seekers. To add fuel to the fire, enterprising people began to breed rats for their tails in illegal farms, seeking to enhance their livelihood via the lucrative trade of rat-hunting.

Known as the Great Hanoi Rat Hunt, this case study is a classic example of the Cobra Effect phenomenon, whereby an unintended (and disastrous) consequence arises from a well-meaning solution. More importantly, we are going to talk about the Second Order Effect, a concept that informs everything we know about the Cobra Effect.

What Is the Second Order Effect?

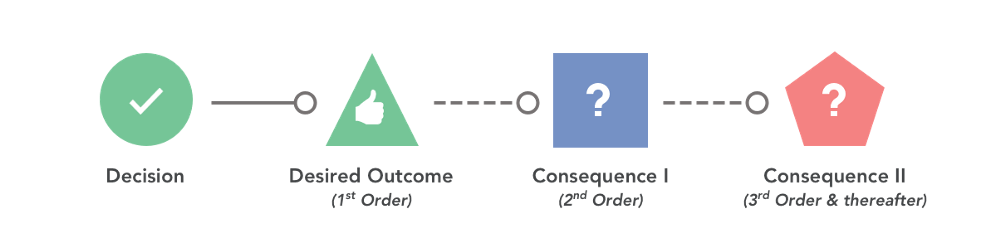

Second Order Effect refers to the idea that every action has a consequence, and each consequence has a subsequent consequence. In other words, this means that a single decision can initiate a series of cause-and-effects, something which we might not have knowledge or control of. Therefore, it can be very difficult for us to predict possible implications of the original decision (unless we are somehow blessed with an all-seeing crystal ball).

As product design and strategy practitioners, we might not necessarily be paying attention to the Second Order Effect when we make certain decisions. This is because we are oblivious to the subsequent consequences (2nd order and thereafter), beyond the desired outcome (1st order) we want to achieve.

How Does the Second Order Effect Affect Us?

Similar to the concept of duality, there are benevolent Second Order Effects and malevolent Second Order Effects. Needless to say, benevolent (and by default, beneficial) Second Order Effects are always welcomed, but we need to be mindful and understand that malevolent Second Order Effects can turn into nasty Cobra Effects if left unchecked.

Image: How the Great Hanoi Rat Hunt transpired. Note how the malevolent 2nd and 3rd Order Effects mutated into Cobra Effect (red background circle).

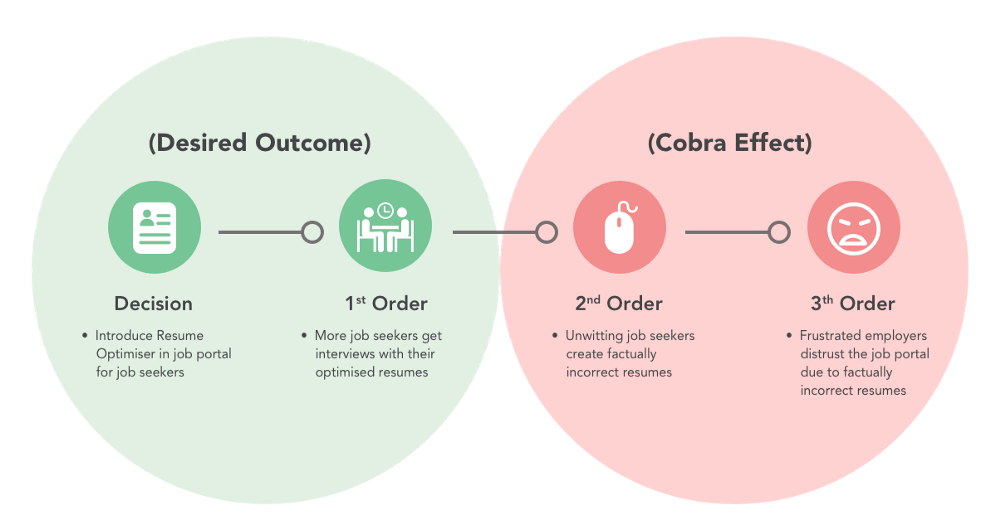

To provide you with another example of a malevolent Second Order Effect, let’s imagine if we were tasked to design a resumé optimizer for a job portal. With this feature, we definitely hope that our job seekers will get a higher chance of interviews from employers (1st order). However, unforeseen possibilities might exist, such as unwitting applicants using the optimizer to create a factually incorrect resume (2nd order), or employers distrusting the job portal due to the massive number of applicants with previously submitted resumes (3rd order).

How Can We Predict the Second Order Effect?

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to predict the Second Order Effect, that's the reality of systemic design. My favorite method is to employ laddering questions during user research sessions. You might have heard of the laddering approach via the popular “5 Whys and 5 Hows” technique, but our aim here is not to focus on the “why” (the root cause of an issue), but rather on how the “how” of a specific goal are achieved.

Going back to the example of the resume optimizer, the following hypothetical “how” questions illustrate how we can identify potential red flags from users:

___________________________________________________________________

Researcher: “How do you think the resume optimizer can help you get a job interview?”

User: “I think this feature will allow me to refine my resume to a point that I will stand out more among other applicants.”

Researcher: “Can you elaborate how?”

User: “Probably the new keywords recommended by the optimizer will showcase my professional ability better. I might be even inspired to add in new keywords which might be related.”

Researcher: "Can you tell me how would you think of new keywords?"

User: “I’ve done a basic course on Microsoft Excel a couple of years ago. Since the resume optimizer recommended me to add Microsoft Word as a keyword, I think I can add Microsoft Excel to my resume…”

___________________________________________________________________

While we can see that the resume optimizer is fulfilling its original purpose of helping the user (1st order), there exists a worrying prospect that the same user might add in information that is not reflective of his true ability (2nd order). Imagine what can possibly happen if the employer interviews our user and discovers his “actual” Microsoft Excel skills…

How Can We Solve the Second Order Effect?

The Second Order Effect is multifactorial by nature. Most of the time, it could be the combination of many things, such as product eco-system, business requirements, or even human nature (in the case of the Great Hanoi Rat Hunt). It only takes a well-meaning decision to start an unknown firestorm.

My advice is to stay calm and think deeper. What we have basically done is to uncover another problem statement which can be solved via good design methodologies. Knowing when and where to anticipate Second Order Effects is important to Systemic Design, a concept that is increasingly gaining traction.

Conclusion

As product design and strategy practitioners, the last thing we want in the world is to have our products misused in the worst possible manner. While answering our users’ needs is important, we should always be mindful of the Second Order effect and the potential implications it might bring.

Let’s think deeper, always!

Ready to transform your business with innovative technology solutions? Contact our team of experts today to discuss how PALO IT can help you unlock value and drive sustainable growth.