“The cool thing about being a designer is that we get to live so many different lives.” This was something I was once told and has stayed with me. In the short span of time I’ve been working as a designer, I’ve had the privilege of designing for — and walking in the shoes of — people living with diabetes, corporate bank staff, parents having to register their children for secondary schools, ship capacity operators, and employment agents for foreign domestic workers.

Designing for such a broad spectrum of people with very different experiences from my own underscores the well-known yet nebulous trait all great designers need: Empathy, the holy grail of UX Design. While designers have a wide range of tools to “build empathy for the user” — empathy maps, storyboards, user personas and such, a question I often think about is — how often is this genuine empathy versus a mere means to an end?

Learning True Empathy From Non-Designers

Wanting to get away from the concept of empathy as a design buzzword, I looked to other professions where empathy is foundational. As Steve Jobs once said, “Creativity is just making interesting connections between things.”

Artwork Credit: Jessica Walsh

1. Learning from actors: Think of the backstory

An actor’s job is to embody and tell the story of a character that potentially bears no resemblance to his or her own life. How does he do it convincingly? Patrick Allen, a former theatre actor, writes about how theatre fundamentally “unveils the complexities of human emotions and explains why people do the things they do — two essential building blocks of empathy.” He shared how after playing Don John in Much Ado About Nothing, he learned about the multi-faceted nature of the villain, including his painful childhood. This helped him understand that there were complex reasons why he behaved the way he did. This impacted how he saw others in his day to day life as well.

Empathy muscle exercise: Think of someone you don’t normally see eye-to-eye with. (This could be anyone from a difficult colleague to your mother.) Fill out an empathy map about them to understand them better. Ask them to walk you through their day.

2. Learning from counsellors: Active listening

I once took a short counselling course, and it fundamentally changed how I listen and respond to a conversation with someone facing a challenging issue. My key learnings were:

- Reflect back / paraphrase what your friend has shared (to acknowledge they are heard)

- Respond with observations or questions, not long personal stories

- Don’t give advice

This has made me more empathetic as it taught me to put their needs first. In a world where we are constantly distracted, active listening is a rare gift. It’s easy to just share a similar story of someone else we know or offer a solution without actually listening to the problem, to make us feel like we have done our jobs as friends or family. These techniques helped me to slowly coax people out of their shell rather than take over their personal space:

Empathy muscle exercise: The next time you have an extended conversation with someone, try not to rush into giving your two-cents’ worth. For example, if your friend says that his department at work is in the midst of letting people go:

Try not to say:

- I know what you mean! Let me tell you about the time I was retrenched…

- Maybe it won’t affect you! You should stay positive!

Instead, try:

- I noticed that you look tired. How has this affected your rest?

- What I’m sensing is that that you’re worried about not being able to provide for your kids. Am I getting that right? Could you share more?

3. Learning from non-profits and charities: Create together

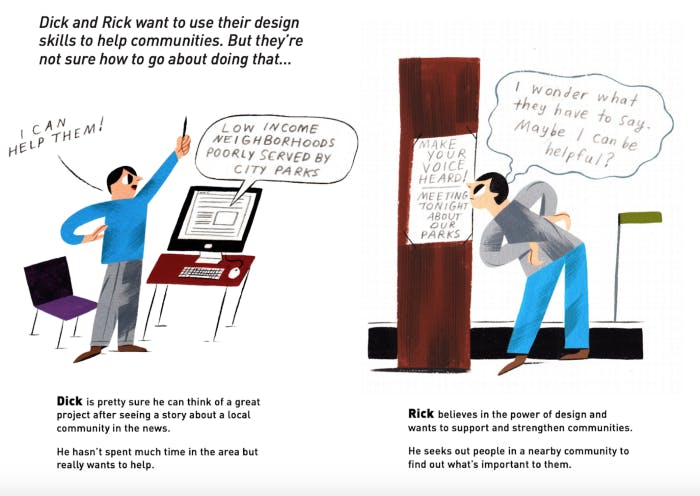

A common thread weaved through many well-established organisations working for social good is the importance of partnering together with people on the ground. This means avoiding the saviour complex of being the superior external party who thinks they know better. Crucial aspects include building relationships with the parties affected, listening to them, generating ideas, and co-creating together.

From Dick and Rick: A Visual Primer to Social Design, by the Centre of Urban Pedagogy, the Equity Collective and illustrator Ping Zhu. It sheds light on how good community-engaged practices advance social justice, and poor practices hurt and field and communities it claims to serve.

Empathy muscle exercise: Think about the last time a decision was made before you were consulted and had affected you. How did it feel? How did it impact you? Think of a situation — whether on a design project, personal project, or even a personal matter where you might potentially be making decisions that affect the lives of others. How can you involve them?

4. Learning from conflict resolution experts: Equalise the scale

In her book, The Art of Gathering, conflict resolution expert and master facilitator Priya Parker writes about a more human-centred and thoughtful approach to gatherings. One concept I found particularly interesting was the idea of equalising your guests. Most gatherings have an imbalance in status some way or another between their guests, real or imagined, such as between a CEO and an intern at a company event, or at party where the loudest person dominates. Parker writes about the different ways to manage this. One interesting example of equalising the scales is setting temporary rules at a dinner party, such as no one is allowed to talk about their job until the end of the night.

Empathy muscle exercise: Think of some ways you can equalise the scale, whether in the context of a group of colleagues, friends, or even in a user interview. What temporary rules can you set — in the form of dress and rules of speaking up?

Conclusion: True empathy takes practice

True empathy is a big step out of anyone’s comfort zone. It’s a muscle I constantly need to exercise. It takes courage and effort. But it is only through building the empathy habit in our day to day lives when making the right decisions during our design work will eventually become automatic, genuine, and natural. Let’s make the effort to become humbler, kinder, and just better human beings — it will only make us better designers.

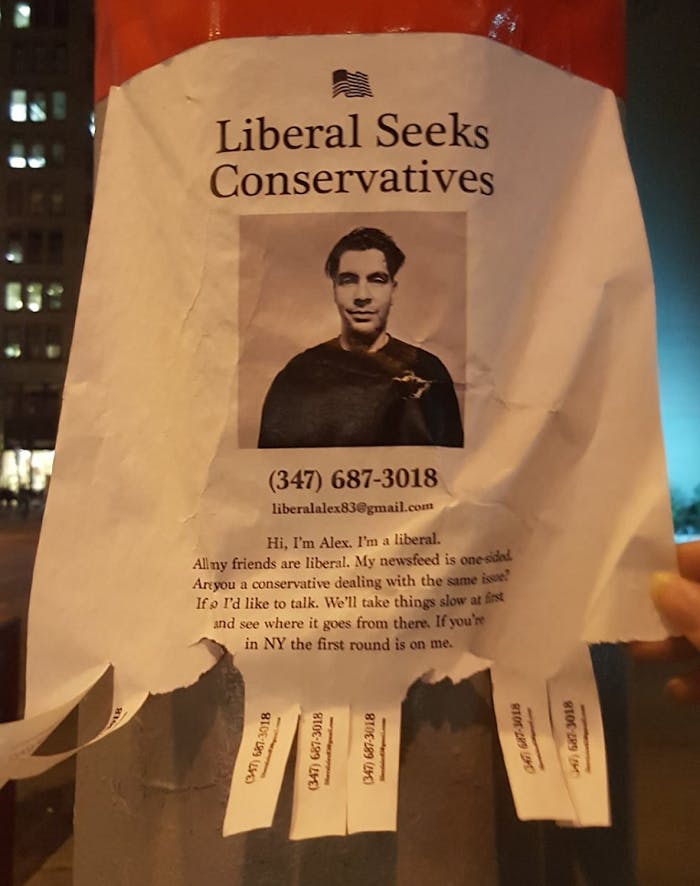

A sign I saw in New York in February 2016, three months after Donald Trump was elected as president.